The Good Place S3E7 "The Worst Possible Use of Free Will"

Spoiler Warning: This reflection contains full spoilers for The Good Place, including retrospective insights and thematic allusions. It assumes familiarity with the entire series and is written from the perspective of a rewatch.

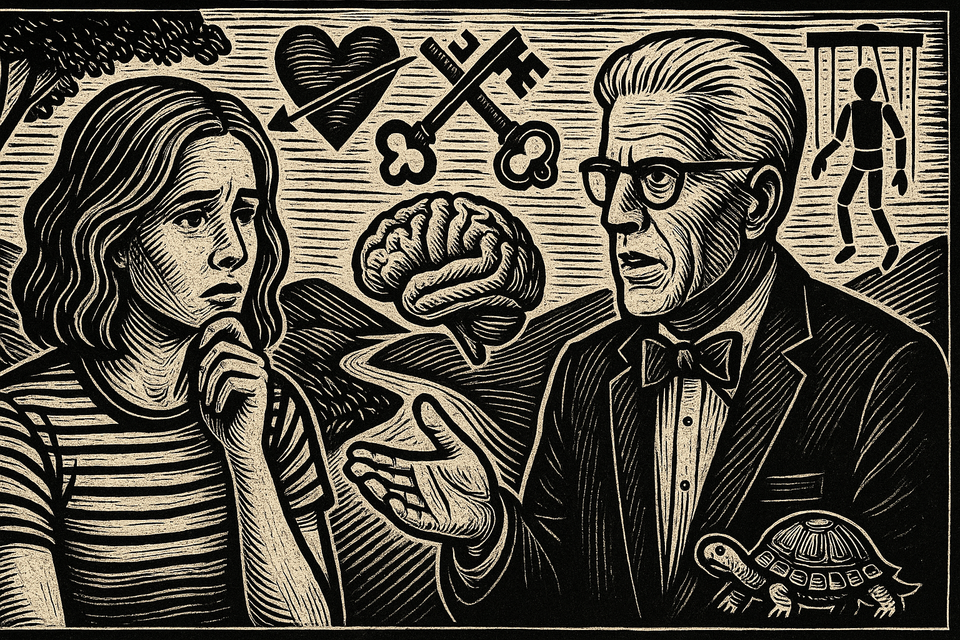

Eleanor’s trip down memory lane in The Worst Possible Use of Free Will begins as a technical experiment and spirals into an existential reckoning. What starts with Michael offering her a chance to see a long-forgotten chapter of her afterlife becomes a fierce debate about whether her choices—especially the tender, terrifying act of falling in love—were ever hers to make. In the space between manipulated circumstance and authentic agency, the episode plants one of the series’ most charged philosophical confrontations, asking whether a person can truly be free when their entire environment has been designed by someone else.

The Good Place and the Battle Between Free Will and Determinism

The heart of the episode rests on a question philosophers have wrestled with for centuries: are we the authors of our choices, or the products of forces beyond our control? Eleanor comes down firmly on the side of determinism. If Michael orchestrated her circumstances, if the environment was engineered to push her toward Chidi, then any feelings she developed must be suspect—proof, in her mind, that she is incapable of loving on her own terms. Michael counters with a more hopeful reading: that even within a designed system, Eleanor made real, unplanned choices. His evidence is a memory from the very first neighborhood, where she confessed she didn’t belong. That moment, he argues, was unscripted—her own leap toward honesty. The tension between them is less about abstract theory than about Eleanor’s defense mechanisms; rejecting free will is safer than confronting the vulnerability that comes with believing her feelings are genuine.

Turtles All the Way Down: Eleanor’s Infinite Regress

Eleanor pushes her skepticism to its logical extreme: if Michael could manipulate her into loving Chidi, what’s to say Michael himself isn’t being manipulated? Maybe he’s just a pawn in some even more elaborate torture scheme run by a bigger, meaner demon. In that framing, the chain of control has no natural endpoint—each supposed free agent might be subject to an unseen hand, ad infinitum. It’s the “turtles all the way down” problem applied to moral agency: every layer of autonomy collapses under the suspicion that there’s always another force pulling the strings. For Eleanor, this isn’t idle speculation—it’s a way to avoid the terrifying responsibility of believing her choices are her own. If every decision is just another domino tipped by someone else, then love, guilt, and change are all illusions, and nothing truly rests on her shoulders.

Freedom in a World of Locks and Keys

While Eleanor and Michael spar over metaphysics, events elsewhere threaten to make the question of free will more than a thought experiment. In the Bad Place, Shawn’s crew quietly constructs an illegal portal to Earth—an open door in a universe where movement between realms is tightly controlled. Against this backdrop, it’s Eleanor who floats the idea that she and the rest of the Soul Squad might be the only truly free beings in existence. They alone understand the artificial nature of their surroundings and the manipulations that shaped them, giving them a rare vantage point from which to choose consciously. In a cosmos full of invisible boundaries, that knowledge itself becomes a kind of master key.

Choosing to Choose

By the end of The Worst Possible Use of Free Will, Eleanor hasn’t abandoned her skepticism, but something shifts. Her “turtles all the way down” reasoning still hangs in the air, yet the idea that she might be among the only free beings left plants a seed she can’t quite dismiss. If the chain of manipulation can’t be broken, perhaps it can at least be recognized—and in that recognition, acted upon. The episode leaves her in that fragile in-between space: not wholly convinced that her love for Chidi was unforced, but willing to consider that it might be real anyway. In a show where cosmic systems and moral scorecards are endlessly gamed, that tentative step toward owning her choices feels like the freest move she’s made yet.

Comments ()