Alien (1979): Silence, Survival, and the Shape of Fear

Spoilers throughout for Alien (1979).

Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) is a film of rare patience. Released in the wake of Star Wars but cut from a different cloth, it trades spectacle for dread, turning deep space into a haunted house and a workplace hazard. The premise is straightforward: the crew of the commercial vessel Nostromo, awakened mid-journey by a mysterious signal, investigate a derelict ship and unleash something they cannot contain. What distinguishes Alien is less the story itself than the manner of its telling—spare, deliberate, and charged with menace. Seen today in its meticulous 4K restoration of the original 1979 theatrical cut, the film reveals both its craftsmanship and its enduring philosophy: terror thrives in silence, and survival belongs to those who heed it.

Part of that endurance comes from the ensemble, a cast that grounds the terror in ordinary human texture. Sigourney Weaver, in her breakout role as Ripley, brings a quiet authority that grows sharper as the crisis deepens. Tom Skerritt’s Dallas projects weary competence, while John Hurt makes Kane’s fate both inevitable and wrenching. Ian Holm’s Ash embodies the hubris of science turned sinister, and Veronica Cartwright gives Lambert’s unraveling a raw, human edge. Together they form a crew that feels less like archetypes and more like co-workers trapped in a nightmare—smoking in the break room, bickering over pay shares, and slowly realizing their expendability.

Silence and Darkness

What lingers most in the early stretches of Alien is not the monster but the quiet. Scott begins with a patience rare in science fiction, drifting the camera through empty corridors while faint, uneasy music swells underneath. The ship hums with low pulses, computer beeps echo in sterile patterns, and footsteps seem swallowed by the air. These slow, deliberate passes through the ship do more than orient us—they map the terrain where the terror will unfold. The corridors feel like hunting grounds, every shadow a potential ambush, every stretch of silence a trap waiting to be sprung. When the crew finally ventures outside, sound shifts entirely: near silence gives way to the howl of alien wind, as though the void itself were screaming. In these contrasts, silence becomes a weapon, holding the audience in suspense until the smallest noise feels like a threat.

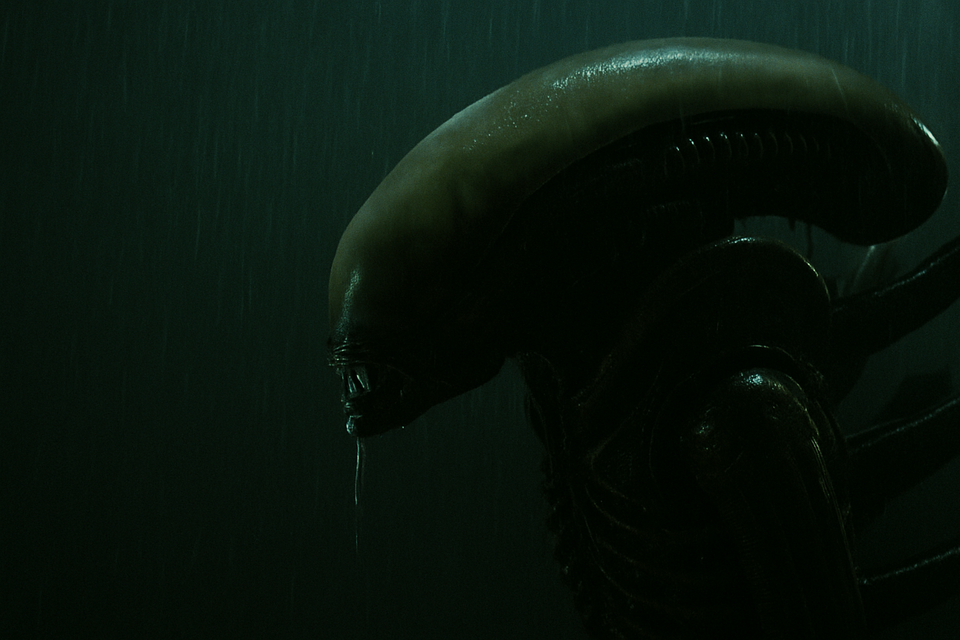

If silence defines the soundscape, darkness defines the look. The Nostromo is never brightly lit; it is carved into pieces by lamps, consoles, and narrow slats of illumination, leaving most of the frame in shadow. That obscurity works two ways. It disguises the limitations of late-seventies effects, yes, but more importantly it makes the ship feel claustrophobic, unfinished, alive. Light falls in fragments across metal corridors that look less like a vessel of exploration and more like an industrial maze, pipes and bulkheads running like veins through its body. The shadows invite paranoia. We cannot see the whole of any space, and we almost never see the alien in full; glimpses and partial shapes are all we are allowed. Suggestion becomes more frightening than exposure. In 1979 this was necessity, but the discipline holds up: four decades later, the unseen still carries more dread than the spectacle of full display.

Mandates and Betrayal

The story unfolds with a kind of cruel logic. The crew doesn’t wake to discovery but to a signal they believe is a distress call. Whatever its source, they have no real choice: company policy makes it clear that if they refuse to investigate, they forfeit their shares. That detail places the whole mission under a shadow of coercion. These are not explorers or soldiers; they are workers bound by contract, and even in deep space their lives are governed by company rules. Only later, when Ripley digs deeper into the ship’s computer, does the truth surface. The signal was not a call for help but a warning. The company already knew, and had quietly rerouted the Nostromo to intercept it. They even replaced the original science officer with Ash, whose hidden directive was to ensure the alien’s retrieval at any cost. “Special Order 937” confirms the betrayal in blunt terms: crew expendable, organism priority. The alien may be the predator that kills them, but the corporation is the reason they were trapped in its path.

What gives the film its staying power is not just the monster but the crew set against it. Ripley emerges as the most capable among them, not because she is stronger or braver, but because she treats procedure and silence with respect. When she tries to enforce quarantine, she is overruled by Ash, and that single breach dooms them all. Her competence grows sharper as the crisis escalates, and by the end she is the only one able to navigate both the alien and the truth about the company. Ash, by contrast, embodies the hubris of science cut loose from humanity. His deference is not to his crewmates but to the hidden orders, and his eventual attack on Ripley reveals how far the corporation’s hand reaches. The others react in more fragile, recognizably human ways—Dallas’s weary attempts at leadership, Lambert’s breakdown under pressure, Kane’s doomed curiosity—but it is Ripley’s insistence on listening, watching, and following the rules that marks her as the survivor. Against the noise of fear and the betrayal of systems, she endures by paying attention.

Ripley, the Final Girl, and the Film’s Legacy

The horror crystallizes in a series of set-pieces that remain startling even after decades of imitation. The facehugger attack plays out with dead silence except for the rush of alien wind, the quiet itself amplifying the obscenity of the image. When the creature later detaches, the crew’s relief feels misplaced, and the chestburster scene follows as one of cinema’s great shocks—Kane convulsing at the table, blood spraying against white fabric, the crew frozen between disbelief and terror. The power of that sequence lies in its rhythm: long stretches of stillness punctured by sudden violence, silence weaponized into dread. From there the alien grows rapidly, and the ship becomes a maze of ambushes. The sounds of the Nostromo—hissing vents, metallic thuds, the faint hum like a heartbeat—blur with the alien’s presence until the whole environment feels hostile.

Much of Alien’s reputation rests on Ripley, who embodies what Carol J. Clover would later call the “final girl.” In the horror films of the seventies and eighties, that figure usually survived by innocence or by chance, her vigilance contrasted against the recklessness of others. Ripley inherits that tradition but reshapes it. She survives not because she is untouched but because she is competent: she listens when others dismiss, she enforces protocol when others break it, and she remains steady as panic overtakes her crewmates. Even Ash, when unmasked as an android, cannot help but admire the alien’s “purity.” What he means is a ruthless clarity of purpose, stripped of morality. Ripley’s version of purity is different—procedural, attentive, grounded in an ethic of survival. That distinction became a model for decades of storytelling, influencing not just the sequels but the shape of horror and science fiction that followed. The film’s blend of silence, darkness, and corporate betrayal created a template for survival horror, echoed in cinema and in video games, and Weaver’s performance carved out one of the most enduring characters in genre history. Seen today, the film remains both terrifying and bracingly modern, its ideas as sharp as its edges.

Verdict

Alien is essential viewing, a film that reshaped both horror and science fiction through silence, shadow, and the slow revelation of terror. Some of its pacing reflects the late seventies, and a few effects show their seams, but those small traces of age only underline how lean and deliberate the film remains compared to today’s CGI excess. Ridley Scott creates dread out of absence, out of what we cannot see, and that restraint keeps the film sharper than most modern imitators. At its center stands Ripley, embodying survival not as spectacle but as endurance, clarity, and refusal to be swallowed. More than forty years later, Alien still teaches us how horror grows in the dark and why survival often depends on learning how to listen.

Comments ()